With regard to acoustic communication, Saccopteryx bilineata is one of the best-studied bat species worldwide. The vocal repertoire consists of various, often multisyllabic vocalization types uttered in distinct behavioral contexts. Saccopteryx bilineata is one of the few mammalian vocal learners known to date (Knörnschild 2014).

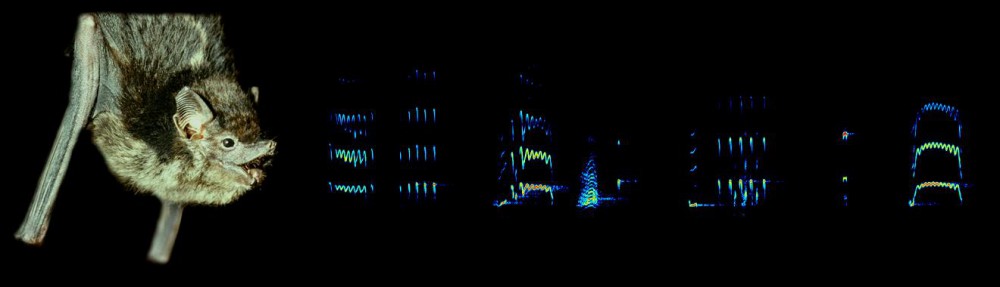

Saccopteryx bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Saccopteryx bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Echolocation

Echolocation calls are not only used for orientation and foraging (Jung et al. 2007), but also for social communication. We have experimental evidence for a strong sex-specific signature and statistical evidence for an individual signature in echolocation calls (Knörnschild et al. 2012).

Echolocation calls (search, approach and final buzz) of S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Isolation call

Isolation calls are uttered by pups to elicit maternal care (Knörnschild & von Helversen 2008). Moreover, they are uttered by young subordinate males to appease dominant males (Knörnschild et al. 2012). Isolation calls encode an individual signature which facilitates mother-offspring recognition (Knörnschild & von Helversen 2008). In addition to the innate individual signature, isolation calls also encode a group signature that is acquired through social modification, a form of vocal production learning (Knörnschild et al. 2012). Moreover, isolation calls also encode an age signature (Fernandez & Knörnschild 2017). Interestingly, the age signature is encoded in a different syllable type than the individual and group-specific signatures.

Isolation call of S. bilineata pup (© Knörnschild).

Isolation call of S. bilineata pup (© Knörnschild).

Maternal directive call

Mothers sometimes respond to isolation calls of young pups with directive calls (Knörnschild & von Helversen 2008), especially when pups make their first flight attempts in the day-roost.

Directive calls of S. bilineata mother (© Knörnschild).

Babbling behavior

Pups produce long bouts comprising of different adult vocalization types. Presumably, this babbling behavior facilitates the acquisition of the adult vocal repertoire (Knörnschild et al. 2006). Vocal ontogeny and pup babbling is the focus of the research of my postdoc Ahana Fernandez.

Babbling bout excerpt of a S. bilineata pup (© Knörnschild).

Babbling bout excerpt of a S. bilineata pup (© Knörnschild).

Territorial song

Males produce territorial songs mainly at dusk and dawn to repel male competitors and defend their territories (Behr & von Helversen 2004). Territorial songs indicate male quality; males that sing more often and with lower peak frequencies have higher reproductive success than males that sing less often or with higher peak frequencies (Behr et al. 2006). Moreover, we have experimental evidence that low-frequency territorial songs elicit a greater couter-singing response than high-frequency territorial songs, indicating that the former are perceived as a greater threat by male competitors (Behr et al. 2009). Male song production increases with increasing male-male competition (Eckenweber & Knörnschild 2013). Territorial songs encode an individual signature and, to a lesser extent, a group signature (Eckenweber & Knörnschild 2013). During ontogeny, pups learn territorial songs from scratch by the imitation of adult tutors (Knörnschild et al. 2010). At dawn, territorial songs act as acoustic beacons which enable females to locate new colonies (Knörnschild et al. 2017). This is especially important when subadult females disperse from their natal colony.

Territorial song of a male S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Territorial song of a male S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Courtship song

Males produce long and complex courtship songs to woo females (Behr & von Helversen 2004). Courtship songs are produced year-round but are especially elaborate during the mating season (up to an hour long). The syntactical structure of courtship songs is part of the ongoing Ph.D. thesis of Maria Eckenweber.

Courtship song excerpt of a male S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Courtship song excerpt of a male S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Whistle

Courting males produce whistles during conspicuous hover displays (Behr & von Helversen 2004). Females often respond with screeches to male whistles.

Male whistles and female screeches of S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Male whistles and female screeches of S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Screech

Screeches are produced by both sexes during aggressive encounters. Moreover, females often screech in response to male whistles during hover displays (Behr & von Helversen 2004).

Screeches of a female S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Screeches of a female S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Distress call

Distress calls are produced by both sexes under extreme physical distress, e.g. being caught by a predator. Saccopteryx bilineata utter long bouts of distress calls consisting of three different syllable categories: buzz syllables with a tonal part, pure buzz syllables, and pure tonal syllables. As in other bat species, distress calls elicit phonotaxis. Saccopteryx bilineata are attracted to distress call playbacks within the day-roost and in proximity to it, but not at a foraging site. Hence, the bats adapt their responsiveness towards distress calls depending on the social relevance in which distress calls are broadcasted (Eckenweber & Knörnschild 2016).

Three syllable categories uttered in distress call bouts by S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Three syllable categories uttered in distress call bouts by S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Bark & Chatter

Barks are uttered by males during mildly aggressive encounters. Moreover, males produce barks to signal alertness even when not actively interacting with conspecifics. Chatter sequences are uttered by both sexes when roosting calmly in the day-roost (Behr & von Helversen 2004).

Barks and chatter of S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Barks and chatter of S. bilineata (© Knörnschild).

Sonograms depict frequency as a function of time (1,024-point fast Fourier transform, 100% frame size, Hamming window with 75% overlap).